- Home

- John Feffer

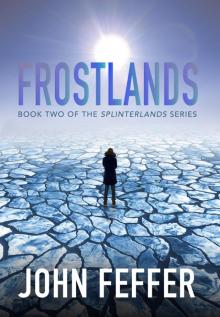

Frostlands

Frostlands Read online

FROSTLANDS

FROSTLANDS

John Feffer

© 2018 John Feffer

Published in 2018 by

Haymarket Books

P.O. Box 180165

Chicago, IL 60618

773-583-7884

www.haymarketbooks.org

[email protected]

ISBN: 978-1-60846-949-9

Trade distribution:

In the US, Consortium Book Sales and Distribution, www.cbsd.com

In Canada, Publishers Group Canada, www.pgcbooks.ca

In the UK, Turnaround Publisher Services, www.turnaround-uk.com

All other countries, Publishers Group Worldwide, www.pgw.com

This book was published with the generous support of Lannan Foundation and Wallace Action Fund.

Printed in Canada by union labor.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my brothers Jed and Andy, who taught me

to make the world a better place.

Table of Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Chapter One

I’m evaluating the signs of blight on the tomato plants in our greenhouse—a brief, head-clearing break from my research project—when my wristband pulses orange. I barely glance at it. I’m more worried about the tomato crop.

Orange alerts are not uncommon in Arcadia. It might be a lone wolf who sees the bright yellow solar paint on our silo and assumes our community is easy pickings. Or perhaps it’s a band of survivalists in search of new digs. If we’re lucky, it’s just a computer glitch or an old, deaf buck that doesn’t register the high-frequency signal the barrier emits. Orange means that the sensors on the outer perimeter wall have registered an attempted incursion. As soon as our wristbands change color, our defense corps begins its preparations, even though the automatic defenses almost always take care of trespassers. I’m no longer one of the regulars. I’m an excellent shot for an eighty-year-old, but I only shoulder a weapon these days for the annual deer cull. The rest of the time I’m here in the greenhouses—or in the classroom or my lab.

The tomato blight is fungal—Alternaria solani. Untreated, it could substantially reduce yield. Fortunately, at this stage it’s still containable. I’ll need to adjust the ventilation to reduce the humidity, and we’ll have to be more careful about the soil we use since we can no longer rely on a winter freeze to kill the spores. In the meantime, it’s just a matter of removing the discolored leaves. I can deal with all three beds of Sun Golds and still have time to finish up in the lab before dinner. As the manager of Arcadia’s greenhouses, I’ve conducted a low-intensity battle for more than a quarter-century against blights of all types. We’ve sustained some casualties along the way, but we’re definitely winning the war. We have fresh vegetables all year long while the rest of the world has to put up with an unrelieved diet of seaweed.

Before I can set to work in earnest on the afflicted plants, though, my wristband pulses again. I look down, expecting it to fade to black. Instead, it turns red.

That gets my attention. I haven’t seen a red alert in more than a dozen years. Red is serious indeed.

As quickly as my calcifying knees permit, I hurry out of the greenhouse and head for the inner perimeter wall, Section A, to take my assigned place. Thanks to the quarterly drills, I know exactly where to go, even though it’s been a long time since the last red alert.

Fortunately, my knees don’t have far to go. Section A is a utility shed approximately fifty yards from the greenhouse. It looks harmless in its rundown state, the corrugated tin siding streaked with rust, the roof dented from a fierce hailstorm years ago. Housed inside is some supplemental farm equipment: a rototiller and plastic sheeting for the late-winter crop. Underneath a dusty hook rug, though, a trapdoor leads to a room containing much of Arcadia’s computing power. This basement bunker is enclosed in enhanced concrete, protecting it from virtually all forms of conventional attack. Section A is one of the most important places in Arcadia, but we prefer not to call attention to it. Nothing sends a message of unimportance like an eighty-year-old sentinel.

Outside the shed, I’m greeted by Bertrand, glowing green.

He gives me a half-hug, his gun slung over one shoulder. “I’m hoping it’s just a computer malfunction.”

I fix my hair in a ponytail and select a weapon from the cache leaning against the shed’s tin wall. To be candid, I can no longer operate heavier firearms. My capacities are winking out like stars in the night sky as the dawn approaches.

I ask Bertrand, “Do you know where the breach is?”

Red alert means the outer perimeter wall has been breached. If the red turns bright pink, someone’s gotten through the inner perimeter as well. That’s never happened, not since the initial wave of attacks nearly two decades ago. In the wake of worldwide crop failures in the late 2020s, those were what turned Arcadia from a peaceful intentional community into an armed compound.

Bertrand shakes his head. “Just the usual orders. Shoot anything that doesn’t glow.”

We take up our positions behind an earthwork that doubles as the side of a cistern for rainwater. The inner perimeter wall, invisible to anyone who isn’t looking at just the right slice of the electromagnetic spectrum, runs through the center of that earthwork. We rest our guns on top of the adobe wall and stare into the distance. Beyond the water in the cistern lies flat, fallow land that will be seeded with spring barley in two months’ time. The fields stretch to a stand of oaks that marks the outer perimeter. The barrels of our guns jut beyond the perimeter screen, as if we were on a parapet. Our inner wall is, in fact, a semipermeable membrane. Anything can pass through it from our side, nothing from the other. Nothing that we’ve encountered, at least.

Somewhere in the zone between the two invisible walls is an enemy. We don’t know who or what it is. We don’t know where it is. The lack of information is deliberate. We are supposed to focus on only one essential element: anything that doesn’t glow.

We glow, Bertrand and I, as do all Arcadia members at the moment. When we go to red alert, our wristbands establish a personal perimeter, and the outlines of our bodies glow a phosphorescent green. We’re not invincible. A direct hit by the latest generation of nanoweapon could probably do a great deal of damage. It’s not something we want to test. We’re expected to stay behind the perimeter unless absolutely necessary.

We’re also not supposed to talk during our sentry time, but I need to know one more thing. “Where’s Lizzie?” I ask him. She’s supposed to be our third guard.

Bertrand doesn’t even look at me. He’s staring past the cistern’s water as it ripples in the barely perceptible breeze of this early winter afternoon. “Reassigned.”

“To?”

“Sector D.”

That’s all the information I need. The breach, I now know, is in Sector D.

Before I can properly process the implications of this, the field in front of us explodes in a frenzy of flying objects. They slice through the air above the fallow ground like a flo

ck of swifts.

Bertrand is the first to start shooting, maneuvering his rifle expertly as if drawing a bead on targets at a firing range. I’m slower on the uptake, but soon my rifle’s humming, too. I’m not quite sure what I’m trying to hit, though they look like compact metallic birds zipping twenty to thirty feet above the ground. All I know is that they’re not green. They’re not part of our defenses. It’s happened so fast that it doesn’t even occur to me that we shouldn’t be shooting at all. Our automatic defense should be handling drones like these.

And then it’s over, almost before it’s begun. The field beyond the cistern is littered with shredded metal, sparkling like a crop of aluminum foil in the weak winter sunlight.

Suddenly the debris vanishes. Bertrand takes a surprised breath in.

I know instantly what’s happened. I’ve read about these new delivery systems, which are solids only at extremely low temperatures. As soon as a remote kill switch is triggered, their previously shielded surfaces come in contact with the atmosphere, turn chemically unstable, and—sub-limating from one state to another—transform into water vapor. If Bertrand and I were to venture onto the battleground, we would find nothing left of these polymers but a few drops of dew on the grass.

I look at him. He’s no longer green. I glance at my watch. It has returned to its default shade of onyx.

“What was that?” Bertrand asks. Only now, after the emergency has passed, do I notice that his fingers are trembling.

“I don’t know,” I say. What I do know is that this was no conventional attack. The paramilitaries and survivalists in these parts have drones, but nothing like what we’ve just seen.

We stow our guns in the underground cache next to the shed. We know the drill. We must report to the Assembly Hall for a meeting in ten minutes.

Now that the adrenaline rush has subsided, I’m again feeling my age: the joint ache, the muscle strain, the fatigue. For an eighty-year-old, I’m in good shape. A four-decade regimen of weight training, yoga, aerobic exercise, and proper diet enables me to keep up with people twenty, even thirty years my junior. I’m not ready for what passes for retirement here in Arcadia.

Sometimes in the ecstasy of the moment, when I’m completely absorbed in my research, I forget my age altogether. All it takes, however, is a glance down at my hand, cracked and spotted like the outside of a baked potato, and I remember that I’m one bad fall, one hip fracture away from the downward slide that will make me a burden to the community. Arcadia doesn’t have the luxury of expensive life-extending services. When the end comes, it comes swiftly, hastened by artificial means if necessary.

As we walk over to the Assembly Hall, I look at Bertrand’s fingers. They’re still trembling slightly as he runs a hand through his hair, and they come away slick with sweat. I’m surprised. Bertrand is a Capture, but from so long ago that most of the younger generation think he’s an OM, one of the Original Members of Arcadia. Although he’s been a quiet engineer during his time here, he was once one of the more militant members of the Quebec Wolves, participating in at least two raids on us before we captured him. He’s no stranger to violence.

It’s largely because of me that Bertrand is here in the first place. Though it’s not something we’ve ever talked about, I suspect he knows it.

He came to us during the initial attacks of the early 2030s. In that hectic period, when our identity and very survival were at stake, Arcadia was divided into two camps— and me—when it came to dealing with the attackers we captured. The pacifists were pushing a policy of catch-and-release: expose the raider to Arcadia, then turn him or her out into the wilds with the gospel of our community. The realists preferred simple annihilation. The raids were, after all, taking their toll in energy expended and injuries sustained, and they argued for a brutal deterrence policy.

I was, as usual, an outlier. The pacifists were too naïve, I thought, while the realists offered a solution no better than the world outside. I proposed a third option. We would design systems to repel attacks. If confronted with a major breach, we would kill as necessary, but always capture one person, whom we’d deprogram, reeducate, and integrate into Arcadia. The Capture would become one of us. In this way, we would constantly test the strength of our community, diversify our gene pool, and send a message of strength through compassion to the outside world.

Having assimilated Bertrand, for instance, we encouraged him to contact his former colleagues in the Quebec Wolves. All attacks from that quarter soon ceased. Both the pacifists and the realists were mollified. We’d lost an enemy and gained an engineer.

As for Bertrand, he married the widow Morris and they soon had a daughter. His wife died two years ago from cancer. Their daughter Lizzie, only eighteen, has recently taken charge of our AI program, which also extends to the automated defenses. She’s part of Arcadia’s second generation, the whiz kids who give me some faint hope for the future. Bertrand, meanwhile, is so well integrated that he now serves on the Community Council.

“Are you okay?” I ask him.

He surreptitiously wipes his fingers on his pants. “It’s been a long time since combat. Brings back some unpleasant memories. I just want a quiet life.”

“That’s all anyone wants.”

I’ve often pondered the difficulty of being a Capture. When we were arguing over the policy, the realists insisted that, human nature being immutable, anyone we brought into the community would remain a potential rogue element. We could deprogram and reeducate all we wanted: at some deep level, the Captures would still harbor the urge to destroy us.

“If that’s how we feel about Captures,” I said at the time, “then we might as well pack up Arcadia and go our separate ways. Our community is based on the premise of change. If we can’t change one person, how are we going to change the world?”

Some of the realists grumbled—deep down, they weren’t interested in improving the world, just their chances of surviving in it—but in the end they went along with the majority. I have no idea if Bertrand knows about these debates. He’s a recent addition to the Council. That gives him full access to the archives, but he may never have bothered to replay the relevant discussions. Still, I’m sure that he could sense, particularly in those early days, that some in the community expected him to revert to the man he’d once been. All along I’ve known that Bertrand’s inner life is something else entirely. After what he’s been through, because he has seen the wolf that hides inside Grandma’s bedclothes, he is now the least likely person in Arcadia to take up arms against us.

The Assembly Hall is the only room in the community that can accommodate all 250 of us. When Bertrand and I arrive, it’s already full and abuzz with speculation. Everyone is spooked by the disappearing drones. They don’t understand how those weapons managed to penetrate the defenses in the first place. We take seats in the back. Before we can insert ourselves into the spiraling conjectures of our nearest seatmates, the two community co-chairs call the meeting to order.

Anuradha is the first to speak. “I know that all of you are very concerned about this red alert,” she says in her rich, reassuring baritone. “We are still looking over the data records, but I think I can say with a fair degree of confidence that we’ve identified the digital breach and it won’t happen again.”

Slender in her orange sari, Anuradha cuts as striking a figure as she did when she helped found Arcadia as a young woman in 2022. Now she is in her late fifties, and the thick black hair that falls straight to her shoulders is threaded with gray. She’s confessed to me several times during our evening constitutionals that she’s tired of the burdens of leadership. This is her fifth rotation as co-chair and she wants it to be her last. I can sympathize. I also did five terms as co-chair, and it is a taxing job. In theory, I’m happy for Original Members like Anuradha and me to turn over the keys to the next generation. In practice, I have a few reservations. Which is why I’ve been urging her to stay on for a sixth term, even if it means she won’t be able to

focus on her primary job of livestock management.

The other co-chair, Zoltan, a platinum-haired young man a head shorter than Anuradha, clears his throat as he always does when he’s nervous and preparing to speak. He is serving his first term. He was born and raised in Arcadia, so he knows nothing but this small world of ours, which makes him parochial in his tastes. Such narrowness of focus, however, can be useful. When it comes to the world of computers, he is brilliant, maybe even a genius.

“The breach lasted for no more than ten seconds,” Zoltan says in his high-pitched, breathy voice. “We are now fully back in control.”

“But who was it?” asks someone I can’t see in the front row, and suddenly the audience is again murmuring.

Anuradha puts up a hand and waits patiently for the noise to subside. “We’re not sure yet. But we should have a good idea by the end of the day. The most important thing is: we don’t expect any more attacks in the near future. We handled this one very effectively, which sent a strong deterrent message to whoever launched it.”

“We’ll need a cleanup crew for Section D,” Zoltan adds. “Some of the outer buildings in that quadrant sustained minor damage. And we’ll need the forest maintenance team there as well.”

Bertrand speaks up. “The drones. They disappeared. How did that happen?”

“A sublime polymer,” Zoltan says. “We did manage to prevent one of them from dissolving, though. We’ll see if we can identify its chemical signature and then trace it back to its owner.”

I’m intrigued. I raise my hand to ask about the drones. “How on earth did you manage to—”

Zoltan speaks over me. “If anyone experienced any equipment malfunctions, please come up to us and report.”

“For dinner tonight, the cooks will prepare something special from our latest deer cull,” Anuradha adds. “And I think this would be a good occasion to test the first batch of apple brandy.”

A few routine explanations, plus the prospect of a filling dinner and an evening of drinking, have calmed everyone’s anxieties. They don’t satisfy me, though. When I find Lizzie, I’ll get the real story of what happened in Section D.

Frostlands

Frostlands